Reading Japan: From Hokkaido to Okinawa

Letters from Japan, September 2025: a fast-paced trip across Japan featuring books to accompany your travels, organized by city and region.

Good evening from Wakkanai, Japan’s northernmost city, whose undeniable lack of aesthetic appeal feels almost intentional, serving to amplify the beauty of the country’s arguably most picturesque island, Rebun, which lies right across the water, only a two-hour boat ride away.1

When choosing the destination for this most recent hiking trip, I set two conditions. First was to find somewhere that was cooler than Tokyo. A requirement that unhelpfully narrowed down my choices to virtually every other place on earth that is not Tokyo, which this year took the humidity to such a degree that the city feels less like a place to live and more like a laboratory built to test the limits of the human body.

The second condition, as vital as the first, was to find a place with no recent bear sightings or attacks. Due to a record number of sightings and, unfortunately, attacks observed all through Japan this summer, this second condition ruled out many of the obvious choices on the four main islands, except for Kyushu, where the bear population went extinct decades ago, and smaller islands off the mainland, where the bears, despite being excellent swimmers, rarely bother to cross.

Although I was initially tempted to revisit Yakushima—Kyushu’s beloved hiking heaven—in the end, the pair of Rebun and Rishiri Islands, off the northern coast of Hokkaido, felt more attractive as the safest bet for the cool weather. They also kind of met the second condition: Rebun is entirely bear-free, while Rishiri, according to the experts, is “99% bear-free”, a statement needed after a shocking event in 2018 when a brown bear, possibly no longer wanting to put up with the depressive mood of Wakkanai, swam over from the mainland Hokkaido.

This month's letter, however, is not about the heavenly beauty of Rebun Island, which I first visited and wrote about last summer, or the impossibly good-looking peak of Mount Rishiri, especially when reflected in the water. Instead, it offers a high-tempo literary journey across Japan, starting in Hokkaido and ending in Okinawa, with the aim of introducing books that you may enjoy during your travels to all those places.

But before the books and this month`s theme inspired by Alan Booth’s travelogue The Roads to Sata: A 2,000-Mile Walk Through Japan, which I re-read while in Rebun, one quick note about these two remote islands that I just got back from: if you visit Japan during the summer, have no desire to risk death at the increasingly vengeful hands of humidity, enjoy gentle hikes with outstanding landscape scenery made even more perfect by alpine flowers that bloom between June and August, Rebun will absolutely make you happy. Rishiri has, honestly, less to offer in terms of scenery, though perfectly shaped Mount Rishiri, which you can climb up, still makes it a worthy stopover (even the lone bear could apparently not resist).

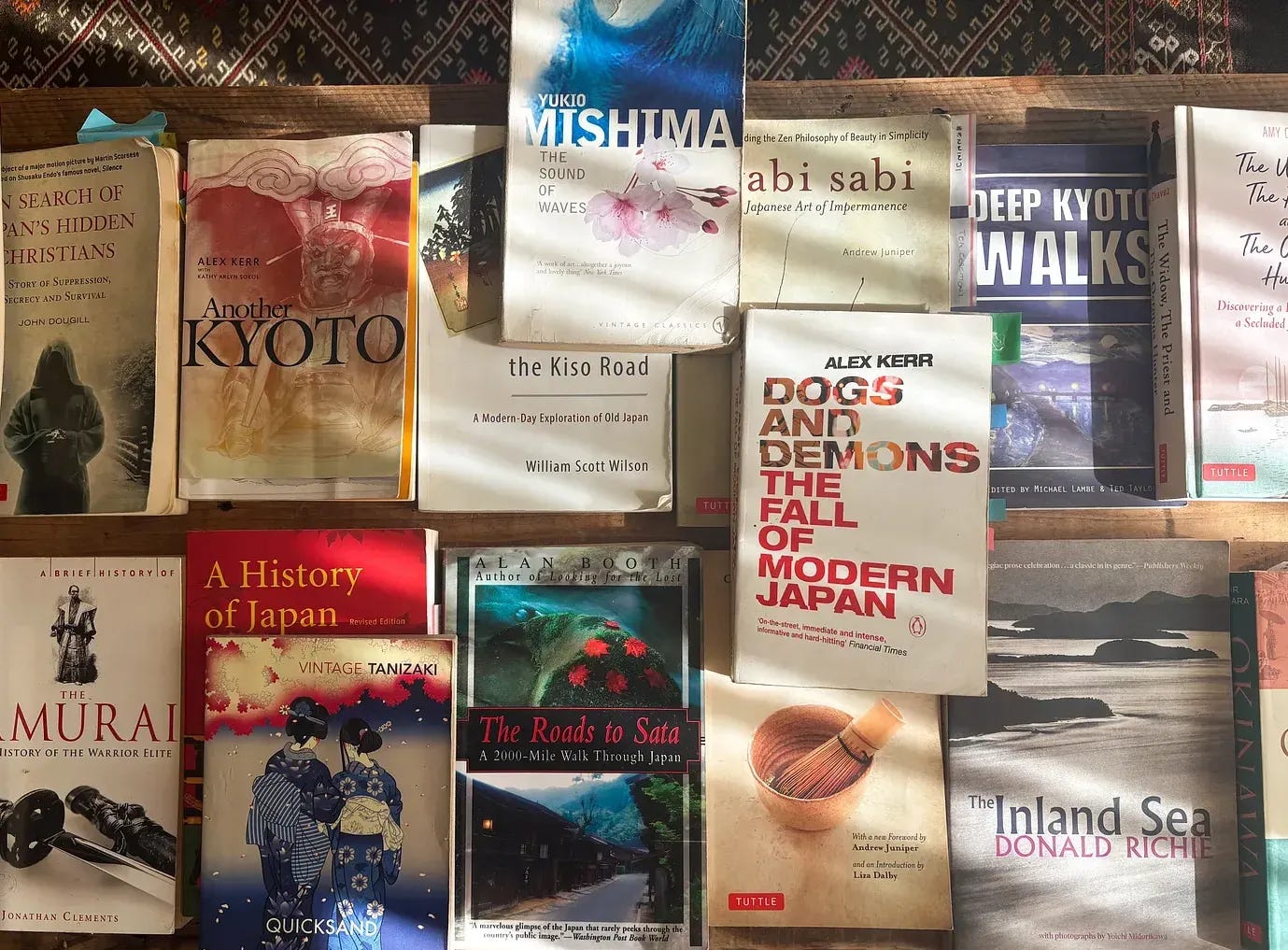

Now, on to this month’s topic and a list of more than twenty books.

Published in 1985 based on a walk that took place in 1977, The Roads to Sata recounts Alan Booth’s journey on foot from Cape Soya, the northernmost tip of Japan near Wakkanai in Hokkaido, all the way to Cape Sata, the southernmost point of Kyushu. Booth`s dry but somewhat comforting and relatable tone, thanks to his resistance to over-romanticizing the sights, his experiences, and his challenging endeavor, coupled with the easily detected affection for the country, makes it a compelling read.

In addition to his tone—and the fact that the humor in the book is mainly at his expense rather than the country`s—what makes Booth’s account of his walk across Japan stand out for me is how well it captures one of the country’s most dreary yet surprisingly rewarding aspects. Step just a little outside the safe and already proven tourism zones, which are naturally or artificially built to deliver the awe factor that we all hope to get out of our travels, and watch all the idyllic expectations you might have attached to rural Japan quickly fade away, forcing you into a new set of architectural, social, and infrastructural realities. This new reality, often at odds not only with the country`s perceived status as a high-tech nation but also romantic notions attached to rural life in developed countries (the rolling green hills, picture perfect wooden houses, lack of concrete?), will inevitably lead to unexpected experiences, offering sometimes the most frustrating, and sometimes the most thrilling cases of “be careful what you wish for” when it comes to our never-ending search for “authenticity”.

I was already 40 when I moved to Japan and had traveled extensively until then, but I think my experiences in rural Japan taught me at least as much about what I personally seek in travel as all my previous trips combined. I like to think those experiences, which first destroy the expectations you bring with you and then give you room and tools to build new ones, have made me a slightly more mature traveler.

Although Alan Booth walked the country in 1977 and much has changed since then, I think the sentiment he conveys about travels in deep rural Japan still lingers today, urging you to look more closely without any clear sense of what the reward might be, ultimately pushing you to create your own.

As you might have noticed, re-reading the Hokkaido sections of Roads to Sata during this latest trip, before bed, and remembering Booth`s inconsequential but subtly moving account was a joy (elevated further by the cool weather that required me to close the windows in the evenings). To honor that joy and in the same spirit, I’ve compiled a list of some other books, arranged by city/region from Hokkaido to Okinawa, that may hopefully bring a similar sense of delight to your own travels in Japan.

I’ll quickly jump from location to location, north to south, dropping book names with a short summary of each, both to keep this letter to a reasonable length and to disguise my shortcomings in the book-review department.2

Alan Booth's walk starts at Cape Soya, the country's northernmost point, which I had been a little too lazy to visit despite heading that far up north several times. In the first two chapters, which cover the Hokkaido leg of his journey with stops in small towns like Tomamae as well as larger cities such as Sapporo, Booth never lets us forget the island’s remoteness and wilderness. He refers to Hokkaido as the “outpost” in one chapter, and as the “savage island” in another, and, along with the account of the early days of his walk (full of blisters and limping), delves into the island's history, with a focus on its original settlers, the Ainu, and its centuries of isolation.

In one of the best-known works of fiction set in Hokkaido, Haruki Murakami's A Wild Sheep Chase, the writer similarly taps into the island's remoteness as an atmospheric backdrop for his story, centered on a search for a mysterious sheep. He takes his two protagonists first from Tokyo to Sapporo and then, slowly, deeper into the northern territory, and dials up the level of mystery with each step towards the north.

I am not a Murakami fan, but I am definitely a fan of Hokkaido, which I first became aware of when I read A Wild Sheep Chase many years ago—a book that admittedly does a great job of portraying Hokkaido as an enigmatic place, maybe even more than it actually is.

Leaving Hokkaido behind by hopping on a ferry from Hakodate to cross the Tsugaru Strait to Aomori, we arrive at Tohoku, a region that frequently features in this newsletter. Despite being part of Honshu, Japan`s largest and most populated island, parts of Tohoku often feel even more remote than Hokkaido.

While increasingly gaining the recognition and interest it deserves for its cultural wonders and dramatic landscape, the region, particularly its eastern coast, is unfortunately still mainly known for one of the country’s most devastating natural disasters: the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which struck Tohoku and resulted in more than 20,000 deaths.

David Pilling's book of essays, Bending Adversity: Japan and the Art of Survival, published three years after the earthquake, reads in part as an ode to the resilience of the people of Tohoku and their strong sense of community. Pilling, who served as the Tokyo bureau chief of the Financial Times for nearly a decade, offers insights into the systematic and even historic factors that may have contributed to the tragedy and how the country dealt with its aftermath.

Although I highly recommend Pilling’s book for a whole new perspective on Japan, Alex Kerr's most recent book, Hidden Japan, published in 2023, may be a better option for a more uplifting read about Tohoku. A long-term resident of Japan and a renowned expert on Japanese culture,3 Kerr devotes two of the book’s ten chapters to Tohoku: in one, he travels to Akita Prefecture to explore the origins of Butoh, a Japanese dance theather, and in another, he visits Minami Aizu and the nearby Ouchi-juku in Fukushima Prefecture, a region famous for its thatch-roofed houses—though not as much as Gifu’s Shirakawa-go—hence the title Hidden Japan.

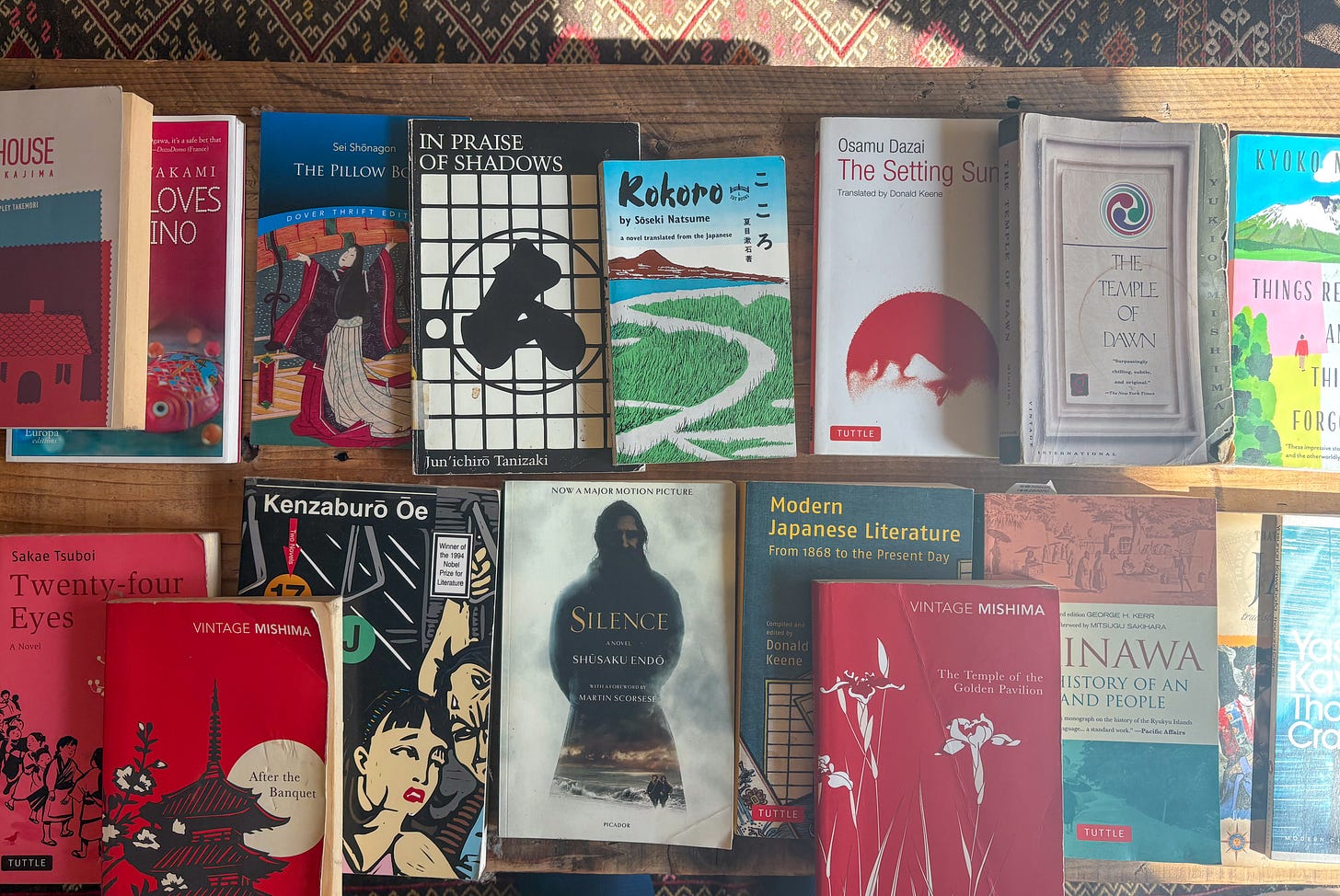

Right next to Fukushima Prefecture in Tohoku sits Niigata Prefecture, part of the Chūbu region and Japan’s primary rice-growing area, which is famous for its sake. The prefecture, more specifically its onsen town of Echigo-Yuzawa, is also the inspiration for one of the most well-known books by Japan’s first Nobel Laureate in Literature, Yasunari Kawabata. Snow Country tells the tragic love story of a married Tokyo man and a local geisha against the backdrop of a snowy hot-spring town—a setting that is not difficult to find in mountainous Japan, and feels as magical in real life as it does in novels and movies.

Our next stop is the Kiso Valley, which stretches along the Kiso River between Gifu and Nagano Prefectures, south of Niigata. The valley is home to a series of towns that are part of the ancient Nakasendo Way, which connected Tokyo to Kyoto during the Edo period via sixty-nine postal towns. Even though I found Walking the Kiso Road: A Modern-Day Exploration of Old Japan, a travelogue by William Scott Wilson, a little clunky and incoherent in how it blends historical facts with the author’s journey from town to town, I would probably still pack it if I revisited the area, but more as a guide than a compelling read.

Just a few hours east of the Kiso Valley lies a tiny little city, home to 15 million people, including me, also known as the capital of Japan. The sheer number of books written about Tokyo or set in the city is enough to warrant a newsletter devoted to the topic. However, since I am not up to the task, I will mention a few titles starting with The Little House by Kyoko Nakajima, which, from the perspective of the housemaid, tells the story of a small Tokyo family, ordinary on the surface but full of hidden intrigues. The story spans both the pre-war Tokyo and the tragedy of the post-war era, when the bombings of March 1945 resulted in nearly 100,000 casualties in the city.

For a more contemporary story taking place in Japan's largest city, Hiromi Kawakami's Strange Weather in Tokyo, which follows the love affair between a woman in her 30s and her elderly former high school teacher, is an engaging, quick read, and makes great use of the city's atmospheric izakayas and parks.

Before wrapping up this undeservedly short Tokyo section, I should also mention Norwegian Wood, one of my favorite books by one of my not-so-favorite authors—yes, Haruki Murakami. The book that turned Murakami into a literary phenomenon in Japan and made him flee the country for a while due to excessive public interest (I may be rolling my eyes a little) centers on a friendship-and-love triangle among three students set against the backdrop of university life in 1960s Tokyo.

The abundance of books about Tokyo, of course, similarly applies to the country's old capital, otherwise known as its most visited, most revered, and, unfortunately, most complained-about city - Kyoto.

If you would like to get a sense of the city in the 1950s, The Old Capital by Yasunari Kawabata, first published in 1962, is an intimate family story that focuses on twin sisters separated at birth. Kyoto is a major character in the book, with some of its well-known events serving as a backdrop to major plot points, such as the Gion Festival held in the city every July.

Another one of Kyoto’s most well-known spots, and its shiniest temple, Kinkaku-ji (the Golden Pavilion), has an entire book devoted to it by Yukio Mishima, one of Japan’s most talented and controversial writers, who committed seppuku after he led a failed coup d'état attempt in 1970.

In The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, loosely inspired by real events (no spoiler: someone sets the temple on fire), Mishima explores the concept of beauty and the destructive obsession that accompanies it through the eyes of a young Buddhist acolyte serving at Kinkaku-ji.

Driven by a much healthier kind of obsession with the city’s architectural wonders, Alex Kerr's book Another Kyoto serves as a highly informed yet accessible guide to the secrets behind the city’s temples, gardens, and other attractions. Organized under various themes, including gates, walls, and tatami floors, the book, in a conversational tone, highlights the details one might otherwise have no way of noticing alone.

Our next stop, Kyoto's big city neighbour, often either despised or praised for being one of the least polished cities in Japan, Osaka, serves as the home base of the Makioka Family, the family at the center of The Makioka Sisters by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki. The family saga is told through the different realities and perspectives of the family's four sisters, who each represent a different aspect of Japanese society and the evolving role of women during one of the most consequential periods in the nation's history, just before World War II and its early phases. Cited as the most important Japanese novel since World War II by The New York Times, the book has also been adapted into a movie. If you have time for only one book before your trip to Japan, Makioka Sisters would be my choice.

Before crossing onto Shikoku Island, a few quick but worthy stops. First, at the Seto Inland Sea, surrounded by seven prefectures and home to hundreds of islands, to mention The Inland Sea by Donald Richie. While I have yet to read Richie`s book, published in 1971, I felt compelled to add it to the list as it is often praised as one of the most moving travelogues about Japan, exploring the small island life in the mid-20th century.

A more recent addition to real-life accounts focused on the Setouchi Islands is The Widow, the Priest, and the Octopus Hunter by Amy Chavez, which focuses on the stories of residents of Shiraishi Island, where she resides. Chavez is also responsible for the wonderful Books on Asia website, which is an unbelievably generous source of information about literature related to Asia, and primarily Japan.

The spiritually charged Kii Peninsula, just east of the Setouchi region, is best known for its network of pilgrimage trails collectively referred to as the Kumano Kodo, as well as for being home to Japan’s most sacred site, the Ise-Jingu Grand Shrine. Long-term Japan resident Craig Mod’s recently published book Things Become Other Things: A Walking Memoir reads partly as a memoir about his youth in the United States and partly as a travelogue covering his extensive walks along the peninsula’s pilgrimage trails. In addition to this recent book, Walk Kumano, Mod’s website dedicated to the pilgrimage routes of Kumano Kodo, inspires one not only to walk the same routes but also to strive for that level of perfection in web content.

One cannot pass through our next stop, Shikoku, without mentioning Lost Japan by Alex Kerr, originally published in 1993. It is a book that I return to very often, mainly for Alex Kerr's admirably modest but poignant writing style. Kerr never sounds preachy, but does not pull any punches when it comes to criticizing governmental policies deemed to have an adverse impact on the country`s cultural wonders. While the book, in a series of essays, touches upon a wide range of topics about Japan, Iya Valley in Shikoku, where Alex Kerr bought a house in the 1970s, is a major character in most of his stories. The book beautifully conveys the feeling of what life was like in this remote corner of Japan in the past, while also delving into the captivating history of the region, which once hosted exiled Heike soldiers who built numerous vine bridges across the valley.

For those planning to walk the famous Shikoku Pilgrimage Route, which covers 88 Buddhist temples throughout the four prefectures of the island, Walking in Circles: Finding Happiness in Lost Japan by Todd Wassel is, despite its tacky name, an engaging read. The author, as he depicts his journey of self-discovery along the route, manages to avoid tired clichés (all reserved for the book's title) and offers an often humorous and honest account of his journey.

For an account of the same walk from a woman`s perspective in 1918 under wildly different circumstances, The 1918 Shikoku Pilgrimage of Takamure Itsue is an excellent choice.

As we approach the end of the list, our next stop is Kyushu Island and one of Japan`s historically most significant cities, Nagasaki.

As I mentioned in a previous letter, I find Nagasaki to be one of the most important cities to visit in Japan for a better understanding of how interactions with other cultures have shaped the Japan of today. Remembered today for the horrific event of 1945, Nagasaki was ironically one of Japan`s first points of contact with foreign cultures starting in the late 16th Century. This short-lived period of openness came to an almost absolute halt in the early 17th century, when the sakoku (closed country) policy, aimed at ensuring self-isolation and blocking foreign influence, was enforced by the Tokugawa Shogunate and strictly observed between 1639 and 1853.

David Mitchell's historical fiction, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, is set on Dejima, which is one of the strangest features of this isolation policy. The artificial island built off Nagasaki in 1636 (and now replicated in the city as a museum) served as a confined space to facilitate trade with select foreign groups, while also ensuring that they remained offshore and isolated from the local population. Mitchell tells the story (complete with forbidden love) of a young Dutch clerk in late 18th-century Nagasaki who becomes one of the few residents of Dejima, which at the time was exclusively reserved for the Dutch traders—the only Westerners allowed to trade with Japan for more than two centuries between 1641 and 1858.

The period of sakoku was also partly a reaction to the powerful religious influence of Jesuit priests who arrived in Nagasaki with the first Portuguese ships in the late 16th century, leading many Japanese to convert to Christianity and earning the city the nickname “Little Rome.” This influence, deemed unwanted by the Shogunate, eventually led to a ban on Christianity that lasted for more than two centuries, accompanied by the cruelly implemented policy of persecution. During this period, secret Christian communities, known as the Hidden Christians of Japan, formed on remote islands off the coast of Nagasaki, including the Goto Islands and Amakusa, to practice their religion in secret, away from the authorities' scrutiny.

This historical period and the region have, over the last decade, gathered increased attention, first with the release of the movie Silence by Martin Scorsese in 2016 telling the story of two Jesuit priests who traveled to Japan during the period when the ban on Christianity was in full effect (based on the book by Shusaku Endo, which is much more layered than Scorsese`s re-telling of the story) and then the addition of 12 sites in the region to the UNESCO World Heritage List under the heading Hidden Christians in Nagasaki Region in 2018. In Search of Japan's Hidden Christians by John Dougill, which reads both as a historical guide and a travelogue, is an excellent book for those planning to visit this fascinating region of Japan and the sites associated with the country`s Hidden Christians.

We have now arrived at our last stop, Japan’s southernmost islands, home to the world’s longest-living people. Despite my endless affection for Okinawa, featured in the July letter, I hadn’t read a book set there until this summer, when I picked up Islands of Protest, an anthology of short stories, poems (that I only partially read) and a play (that I must confess I have not read) by Okinawa-based writers who capture the region’s enigmatic, disconnected, and delightfully strange spirit. Among the seven short stories featured in the book, Island Confinement by Sakiyama Tami is my favorite.

So, this wraps up this month’s letter. As always, thank you for being here and allowing my monthly letters in your inbox. I will be back in a month, hopefully featuring a new destination.

Until then,

Burcu

P.S. In addition to the monthly letters, below is a quick recap of the extra itinerary and planning-focused posts available on the newsletter for monthly and annual subscribers. You can access each one here on Substack or on a single page on my website.4

One Fine Autumn Day in Tokyo (December 2025)

Tohoku Onsen Hopping: Four Nights, Four Hot Spring Inns (November 2025)

Tokyo Eateries: the Non-Gourmet Version (October 2025)

Autumn Colors Trip to Aomori: Itinerary Suggestion (August 2025)

One Fine Day in Kanazawa (July 2025)

Cycling the Shimanami Kaido in Two Days (June 2025)

Japan Trip Planning Q&A Series (three posts) (February - April 2025)

Winter Trip to Biei in Hokkaido (four posts) (January 2025)

Hiking the Kyoto Trail (five posts) (November 2024)

One Fine Autumn Day in Kyoto (October 2024)

Okinawa Diaries: Tokashiki Island (two posts) (September 2024)

Walking Goto Islands (eight posts) (March 2024)

I started drafting this letter in Wakkanai, but I am now finishing it in Tokyo.

Here is an earlier post where I wrote about five books related to Japan, with slightly longer explanations for each book: https://www.lettersfromjapan.com/p/january-in-japan

I refer to three books by Alex Kerr in this post, all covering different aspects/regions of Japan. For a non-Japan-related read, I also highly recommend Bangkok Found: Reflections on the City by him. As I understand, he divides his time between Thailand and Japan.

It requires the password received in the automatic email sent right after subscribing to a paid option.

Great content!! I added many new books to my reading list.

I do have two additional recommendations for Tohoku, which is where I lived.

One of them is Abroad in Japan by Chris Abroad. He is now one of Japan’s biggest YouTubers, but he had a humbler start as a teacher in Yamagata, which he discusses in his book.

Additionally, Isabelle Bird was a pioneering travel writer in the 19th century. Her book details her journey across Tohoku in the year 1878!

Merhaba Burcu! Yazım stilin huzur veriyor. The bear incidents made me a little worried but i think it's a minimum risk for my planned Kumano Kodo Nakahechi hiking upcoming December :)

It's great to read your whole letter slowly and in peace, noted a few books to read on my visit to Japan. Thanks!